Guillaume Rondelet (1507-1566), the grandfather of ichthyology who dissected his own son

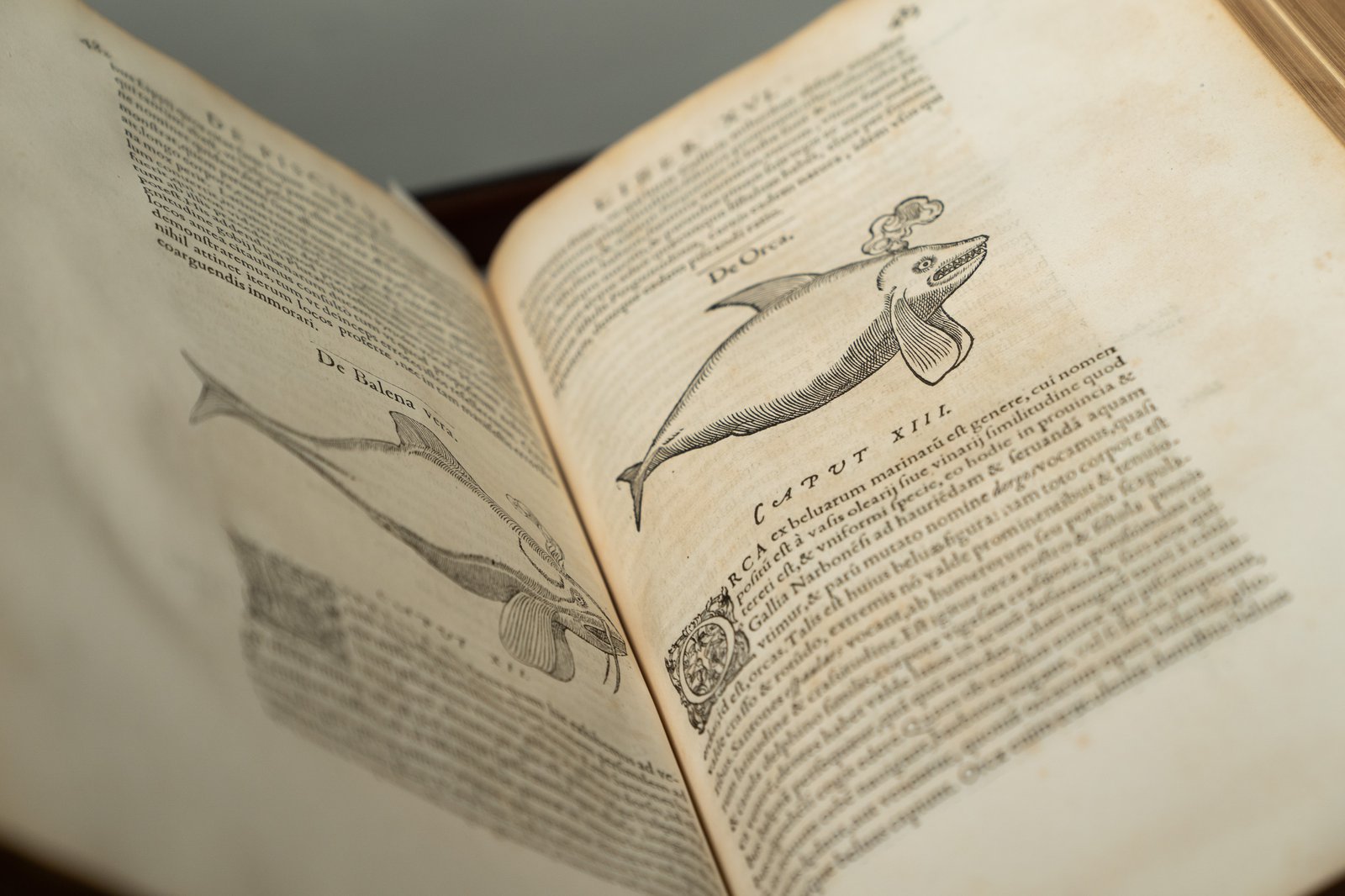

Woodcut of an "orca" from Libri de piscibus marinis, in quibus ver piscium effigies express sunt by Guillaume Rondelet, 1553-1555.

Image: Nick Langley© Australian Museum

Published in parts between 1553 and 1555, Libri de piscibus marinis, in quibus ver piscium effigies express sunt is the oldest book in the Australian Museum Research Library’s collection. Its author, Guillaume Rondelet (1507-1566), led a life of science and scandal.

Guillaume Rondelet's early life and medical career

Born in Montpellier in 1507, Guillaume Rondelet’s father, a spice merchant, died soon after he was born. He was instead raised by his older brother. Rondelet’s childhood was marked by illness, including, supposedly, syphilis contracted from his wet nurse. By the time he was 18, Rondelet was well enough to move to Paris for university. Four years later he returned to Montpellier for medical school, where he was eventually appointed Regius Professor of Medicine in 1545.

During his medical studies, Guillaume Rondelet became fascinated with the relatively new practice of dissection, which at the time was still considered taboo. After establishing the first dissection theatre in France at the university in Montpellier, he scandalised the town by dissecting the cadaver of his own infant son to determine the cause of death, as well as the afterbirth of his twins. This, along with poor management of his finances, may have caused Rondelet to close his medical practice. Luckily for him, Rondelet was able to attract a wealthy patron: Cardinal Francois de Tournon. Consequently, Rondelet left Montpellier to travel with the Cardinal’s entourage as his personal physician.

Travel and Libri di piscibus marinis

Although Guillaume Rondelet was already passionate about natural history, it was through his travels with the Cardinal that he was able to observe many marine animals along the coast, forming the basis of his research for his future masterwork. Unlike many of his contemporaries who relied on second-hand accounts for their zoological compendiums, Rondelet based most of his descriptions of marine animals in Libri de piscibus marinis on his own first-hand observations. Having developed his autopsy skills on human cadavers in Montpellier, he dissected many specimens himself, including marine mammals and small whales. Although his research was more empirical than that of some of his peers, Rondelet still included some questionable species in Libri de piscibus marinis which he had not personally seen, such as the "monk fish", the "bishop fish", and a "leonine sea monster".

Clashes with religion and Guillaume Rondelet's death

Despite his close ties to the Cardinal and a lifelong interest in theology, Guillaume Rondelet also clashed with the Church. For example, when his other patron and friend, Bishop Guillaume Pellicier, was arrested for being sympathetic towards Reformers, Rondelet burnt many of his theological books. In one alleged incident, Rondelet had to hastily retreat from visiting a patient near the Spanish border, as he had come under the religious suspicion of Spanish authorities.

After becoming ill from dysentery, Guillaume Rondelet died in 1566. In spite of the help he received from Catholic benefactors throughout his career, he apparently died a Protestant.

Guillaume Rondelet's legacy

After his death, Guillaume Rondelet’s pupil Laurent Joubert wrote a biography of his life. While Joubert praised Rondelet’s intelligence and scientific brilliance in the fields of natural history and anatomy, as well as his generous spirit, he also described him as careless (both personally and with his writing), bad with money, and an avid lover of women.

Regardless of the proclivities of the author, Libri de piscibus marinis was considered the definitive text for ichthyologists for the next hundred years, with over 250 species of marine mammals described (as was customary for the time, Rondelet made no distinction between fish and other sea creatures). Indeed, four and a half centuries after its publication, it remains a fascinating and impressive work.

References and further reading:

“Rondelet, Guillaume.” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com, 2008, https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/rondelet-guillaume

Constantino, Grace. “Bishops in the Sea for Halloween!” Biodiversity Heritage Library Blog, 31 October 2016, https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2016/10/bishops-in-sea-for-halloween.html

Miane, Asma et. al. “Guillaume Rondelet (1507-1566): Cardinal Physician and Anatomist Who Dissected His Own Son.” Clinical Anatomy, vol. 27, no. 3, 2014, https://mphrc.tbzmed.ac.ir/uploads/113/CMS/user/file/847/1393/8.pdf

Oppenheimer, Jane M. “Guillaume Rondelet.” Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine, vol. 4, no. 10, 1936, pp. 817-834, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44438304?read-now=1&seq=15#page_scan_tab_contents

Romero, Aldemaro. “When Whales Became Mammals: The Scientific Journey of Cetaceans From Fish to Mammals.” New Approaches to the Study of Marine Mammals, edited by Aldemaro Romero and Edward O. Keith, IntechOpen, 2012, https://www.intechopen.com/books/new-approaches-to-the-study-of-marine-mammals/when-whales-became-mammals-the-scientific-journey-of-cetaceans-from-fish-to-mammals-in-the-history-o

Siraisi, Nancy G. History, Medicine, and the Traditions of Renaissance Learning. University of Michigan Press, 2007. Google Books.

Tietz, Tabea. “Guillaume Rondelet and the Aquatic Life.” SciHi Blog, 27 September 2015, http://scihi.org/guillaume-rondelet-and-the-aquatic-life/