The tiny fossil that helps us reexamine the story of how life evolved across our ancient supercontinents

For decades fossils from the northern hemisphere have dominated scientific thinking about how and where species evolved, creating a distorted view of life's history on Earth. Southern hemisphere discoveries are often overlooked and scientific history has been shaped by a geographical bias, as most palaeontological research happens in the "Global North”.

But now, tucked within the palaeontology collection at the Australian Museum, the oldest fossil of a non-biting midge from the southern hemisphere is challenging long-held assumptions about how life evolved across the planet's ancient supercontinents.

© Australian Museum

A new perspective

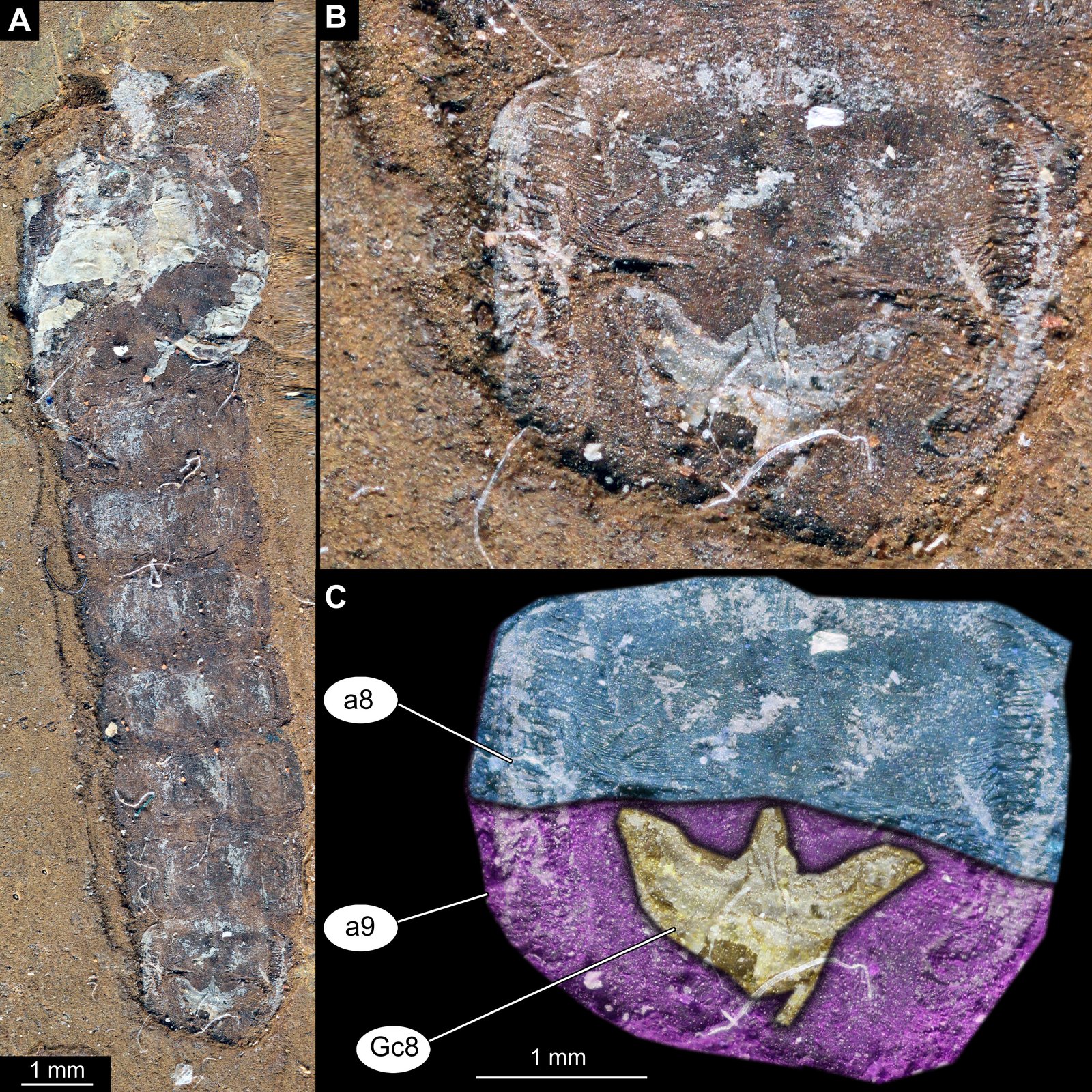

The Australian Museum’s fossilised remains, estimated to be around 151 million years old, were first discovered in the Talbragar Fish Beds in New South Wales and were the focus of a recently published paper in the journal Gondwana Research led by Doñana Biological Station, with help from the Australian Museum Research Institute, UNSW Sydney, the University of Munich, and Massey University.

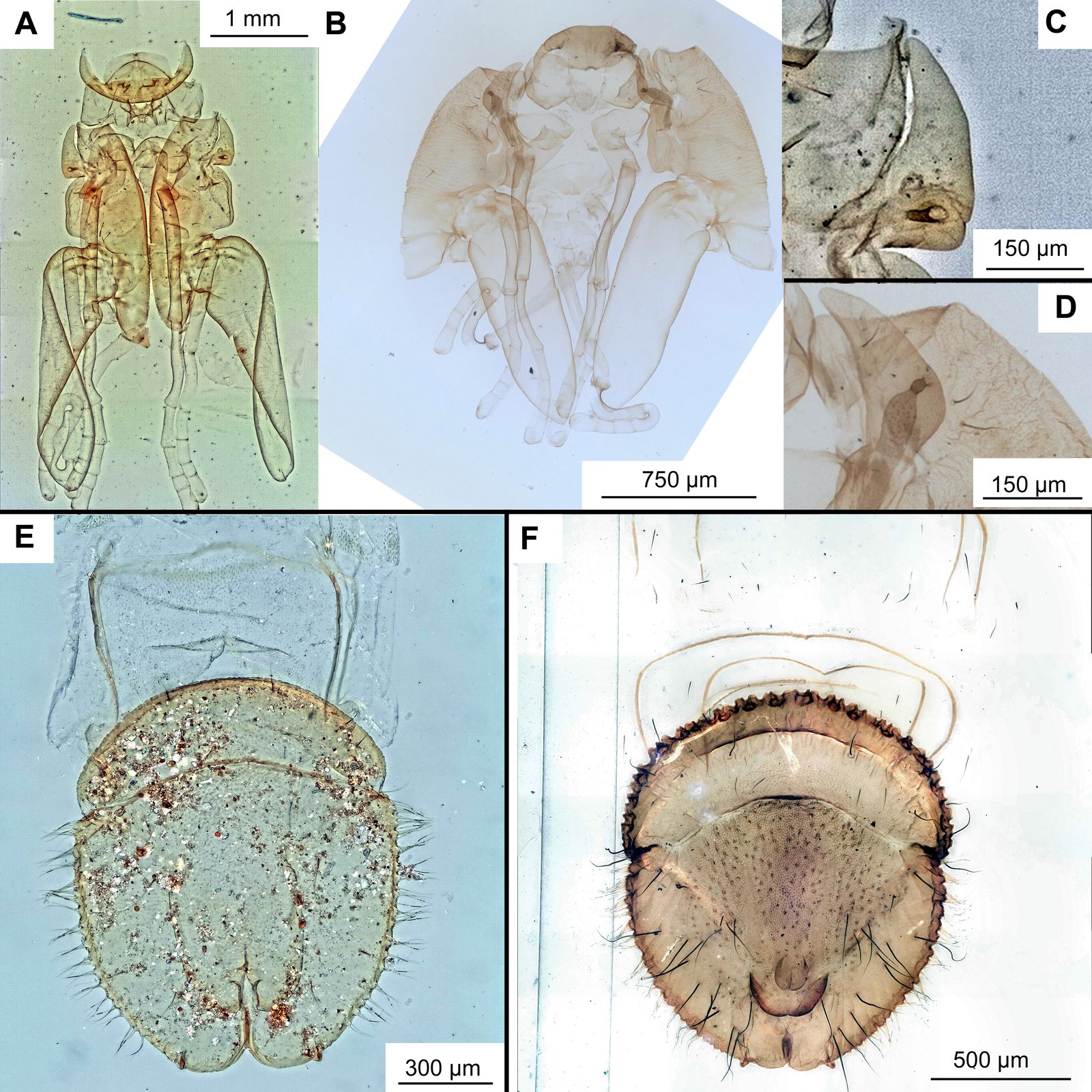

Research into the group of non-biting midges called Podonominae demonstrates the implication of geographical bias in action. Until now, their oldest known fossils came from China and Siberia, leading scientists to assume they originated in the northern supercontinent of Laurasia… But this new Australian discovery suggests otherwise

© Viktor Baranov

Evidence of Gondwana origins

The fossil first came to light at an international conference in 2016, when Robert Beattie, associate of the Australian Museum, presented his research on Talbragar insects. This moment ignited the curiosity of Viktor Baranov, from Doñana Biological Station, and together they began to discuss if they were dealing with some kind of aquatic midge pupae, likely Chironomidae. Focusing on key fossils held in the Australian Museum’s collection, the international collaboration began to investigate the significance of this tiny insect. In February and March of 2020, Viktor came to Australian Museum on the Australian Museum Research Institute collection visiting fellowship. During his stay he worked with the Australian Museum’s team focusing on the undescribed fossils from Talbragar.

The research found the all-important distal end of the abdomen was lacking expected characters like “paddle-like” flippers or long hairs. So, across the next seven years the challenge was to prove if the specimens were just poorly preserved or if something more was going on.

The breakthrough

A eureka moment happened in 2024, when the team realised that the lack of the characters on the distal ends on the rounded end of the abdomen, together with multiple muscle marks, pointed towards the presence of the suction disc.

The available data, derived from a combination of the morphological and molecular evidence, suggests the Podonominae is more likely of Gondwana origin. Around 80% of modern biodiversity of the group is found in the southern hemisphere, mostly beyond the tropic of Capricorn, which also support this hypothesis. The new findings represent critically important information to help us understand where the group originated and how they spread over time.

It all comes down to a suction disc

What makes the Australian Museum’s fossil particularly special is the identification of the suction disc, an adaptation for survival in turbulent water environments, which represents a rare evolutionary feature. Such a specialised adaptation probably could only have emerged if Podonominae had been developing in Gondwana for a significant period, rather than recently migrating there from China or Siberia.

© Viktor Baranov

Rethinking ancient geography

The previous theory that this important insect group originated in Laurasia was based simply on the oldest fossils being found there. As this discovery demonstrates, absence of evidence should spark further inquiry and research. As the fossil record from the southern hemisphere has been less intensively studied, there are gaps in our knowledge that can lead to incorrect conclusions about where species evolved and how they spread.

This Australian midge is a reminder that the southern hemisphere holds crucial pieces of the evolutionary puzzle, and these pieces can fundamentally reshape our understanding of life's history on Earth.

- Dr Matthew McCurry: Curator Palaeontology, Geosciences & Archaeology, Australian Museum

- Viktor Baranov: Doñana Biological Station

© Australian Museum