The sex life aquatic: How sea snakes have overcome the tricks of sex at sea

When you think of “sensitive” lovers, snakes are probably not the first thing that comes to mind. But our new research reveals how important tactile communication is in the sex lives of snakes.

You may be familiar with how snakes on land find a mate, but how snakes find mates underwater has proven to be more elusive. On land, male snakes find mates by “smelling” pheromone trails left behind by females as they move. This, however, is impossible in an aquatic world where these chemicals are diluted and washed away in the waves. In our recently published paper in the Biological Journal of the Linnaean Society, we detail the enlarged touch receptors in the male turtle-headed sea snake (Emydocephalus annulatus), which likely evolved to overcome the challenges imposed by an aquatic sex life.

Turtle-headed sea snake swimming. Footage provided by Jenna Crowe-Riddell

An additional hurdle to finding a mate is that turtle-headed sea snakes can’t see very clearly underwater. They will literally try to mate with just about anything with the vaguest similarity to a female sea snake—sea cucumbers, ropes, even flippers!

Once he does manage to spot a female, keeping track of her without floating away is an incredibly tricky task to surmount when you evolved on land and moved to sea relatively recently. Given the incredible challenges of the sex life aquatic, we hypothesised that male turtle-headed sea snakes may have evolved an enhanced sense of touch to maintain contact with females during courtship.

Underwater tactile foreplay

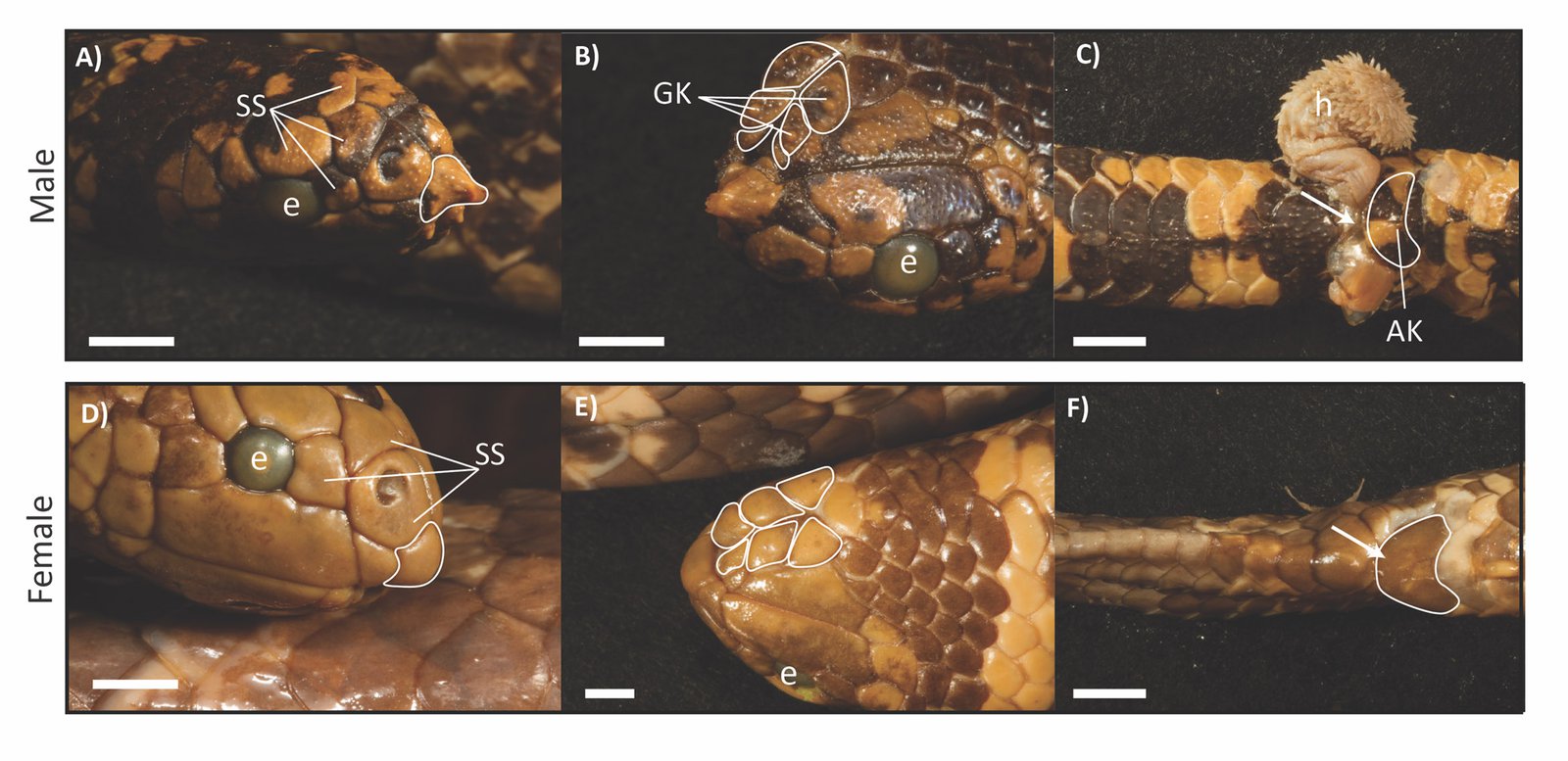

Like many snakes, the faces of turtle-headed sea snakes are covered in tiny bumps. These tiny bumps are, in fact, touch receptors. But when we looked closely at Australian Museum and Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory specimens, we realised that in male turtle-headed sea snakes, they’re really not that tiny at all!

Scale receptor comparison.

Image: Jenna Crowe–Riddell© Jenna Crowe–Riddell

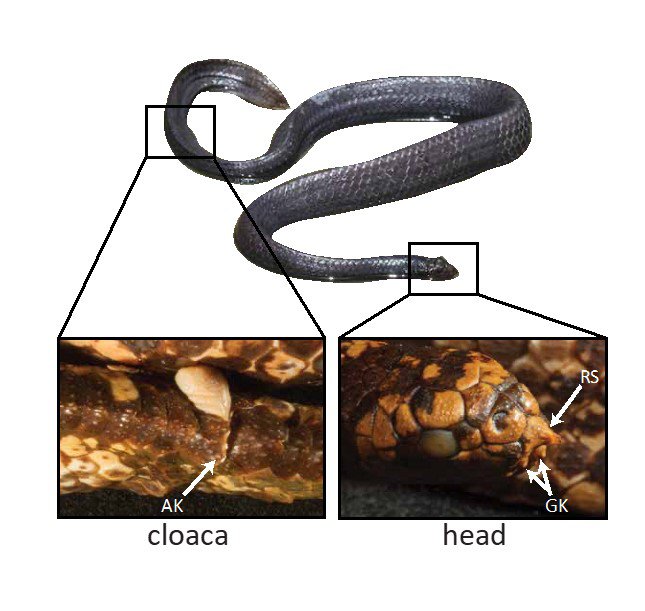

We also found mature males have enlarged scale structures on their snout, chin, and their cloaca (a dual-purpose hole for reproduction and excretion). The location of these enlarged scale structures along the body suggests a role in tactile sea snake courtship.

Positioning of the scale structures on a male turtle-headed sea snake. RS = rostral spine and GK = genial knob.

Image: Jenna Crowe–Riddell, Max Jackson and Chris Jolly© Jenna Crowe–Riddell, Max Jackson and Chris Jolly

The touch receptors on the chin of males ("genial knobs”) have the same specialised cells as those on the face, but the outer bump is four times larger. Their position on the underside of the head gives sensory feedback to the male as he swims above females. With such poor eyesight and difficulty tracking her via scent, these enlarged touch receptors likely help him orient towards the direction of her swimming. Additional and enlarged touch receptors on his anal scales (“anal knobs”) likely provide feedback to help him align his sexual organs with her’s. Genital alignment may seem like a trivial task, but for a limbless noodle creature in a buoyant aquatic world, touch receptors on your parts are essential!

Males also have a conical scale on their snout known seductively as the “rostral spine”. While courting the female, the male will prod the female’s back with this hardened scale. We also investigated the micro-structure of the rostral spine and found it is made of thickened layers of skin with no specialised sensory cells. We think it may simply play a role in piquing the female’s interest in mating with an amorous male.

Similar “tactile foreplay” behaviours have been observed in species of boas and pythons. These snakes have retained a claw that is attached to the remnants of a vestigial hip structure near their cloaca. Like turtle-headed sea snakes, male pythons and boas use this claw to poke and scratch at females to get them in the mood. These courtship behaviours can stimulate beneficial hormonal changes and receptive behaviours in females, which increase mating success for both sexes.

It’s possible that the rostral spine in turtle-headed sea snakes plays a similar role in stimulating females.

Comparison of male and female turtle-headed sea snakes. Males have A) a rostral spine, B) enlarged genial knobs (GK), and C) anal knobs (AK). Males also have A) larger scale receptors (SS). H = hemipene, which is a male reproductive organ.

Image: Jenna Crowe–Riddell and Chris Jolly© Jenna Crowe–Riddell and Chris Jolly

Evolutionary transitions

All sea snakes evolved from Australian land snakes some 20 million years ago. This transition from life on land to the life aquatic involved remarkable and rapid evolutionary adaptations, such as paddle-shaped tails for swimming, glands that excrete saltwater and cutaneous breathing to avoid the diving sickness. Now, our research is beginning to uncover the importance of touch for social behaviours in sea snakes.

While sea snakes are not usually appreciated for their sensitive side, our discovery suggests an enhanced sense of touch evolved to improve communication between individuals. This is especially crucial in an aquatic world, where other sensory signals such as vision and pheromones are diminished.

As our work continues, sea snakes will continue to surprise us with their fascinating adaptations to the underwater world.

Jenna Crowe-Riddell, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia; and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, USA.

Chris Jolly, School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria; Museum & Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin, Northern Territory; and Research Associate, the Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW.

More information:

Jenna M Crowe-Riddell, Chris J Jolly, Claire Goiran, Kate L Sanders, The sex life aquatic: sexually dimorphic scale mechanoreceptors and tactile courtship in a sea snake Emydocephalus annulatus (Elapidae: Hydrophiinae), Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2021; blab069, https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blab069