The fish list: A decade in the making

Home to the billowing sails of the Opera House and the shimmering arches of the Harbour Bridge, Sydney is famed for its magnificent harbour – but what lies beneath the water’s surface? In a recent study, Australian Museum scientists delve into the remarkable biodiversity of Sydney harbour.

In a recent study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin, Australian Museum scientists delve into our incredible fish biodiversity by generating an up-to-date, annotated checklist of all fishes ever recorded from Sydney Harbour – which was no small feat! This new checklist is based on specimens held at the Australian Museum dating back to 1868, as well as newly available citizen science observations, recorded since 2009 via the Australasian Fishes Project and Reef Life Survey. Although absolute numbers of fish observations are important, we wanted more than their names: namely, where and when were these fishes detected, what function they serve in the Harbour, if they are endangered or economically important in NSW, if they could stand to live in some of the more polluted sections of Sydney Harbour and if they like it hot or prefer cooler waters.

© iNaturalist

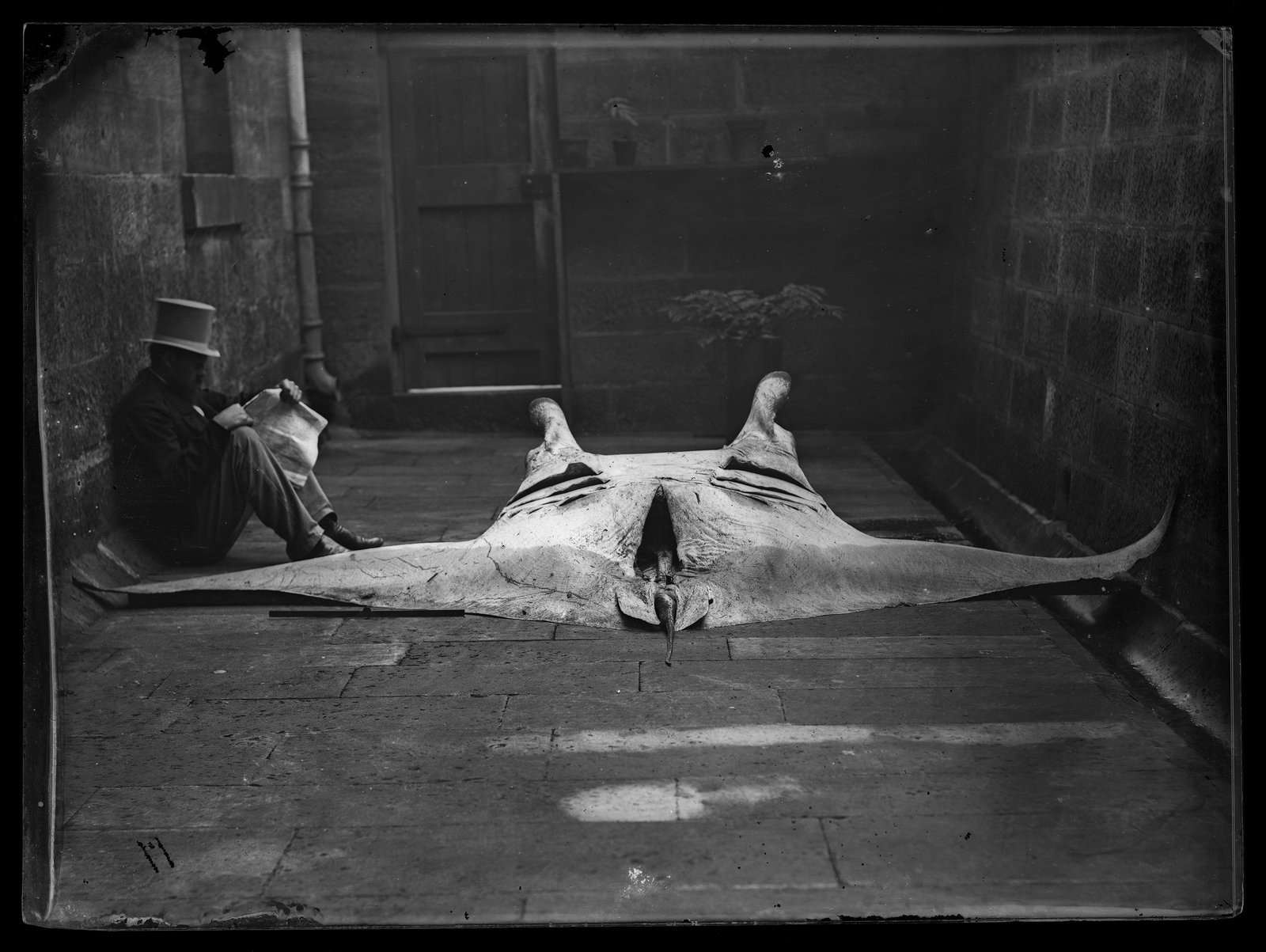

Based on independent data sources, the number of fish species recorded from Sydney Harbour now stands at 675 – an increase of 89 species (15%) when compared to the most recent publication by AM Senior Fellows Dr Pat Hutchings and Dr Mark McGrouther (and colleagues) in 2013. The two greatest increases in fish data records occurred in the 1880s and 1970s; this appears to coincide with growth in the activity of colonial naturalists (1880s) and AM employment of expert ichthyologists with dedicated collection programs and improvement of SCUBA technology in the 1970s. The earliest recorded fish in Sydney Harbour was a Manta Ray Mobula alfredi collected in Watsons Bay, Sydney Harbour. This specimen became our ‘holotype’, an individual of a species that is used to formally describe the species. In 1868, Australian Museum Director Gerard Krefft made this fish famous by naming it in honour of the visiting Prince Alfred from England. Some of these 675 fish species are protected by a variety of national and international laws and treaties including the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Convention on international Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act in Australia. Some of the fishes are also protected in at least one Australian state or territory and include 84% of the most commercially and recreationally important fish species in NSW.

© Australian Museum

The increase in fish diversity over a relatively short period of time can be attributed to newer citizen science programs. Participation in citizen science has exploded in Australia (just think about FrogID!) with increased access to technologies such as smartphones and underwater cameras, as well as slick and user-friendly web platforms like iNaturalist. This increase can also be attributed to the influx and survival of fishes in the harbour with preferences for warmer waters. The East Australian Current (made famous in the film Finding Nemo by the Pacific Green Sea Turtle, Crush, who called out, “Grab shell, dude!”) brings warm water and tropical fish larvae to the Sydney region from the north. Given that we are nestled in one of the hottest of the climate change “hotspots” globally, Sydneysiders should get used to seeing both kelps and corals alongside each other in the harbour with increasing ocean temperatures.

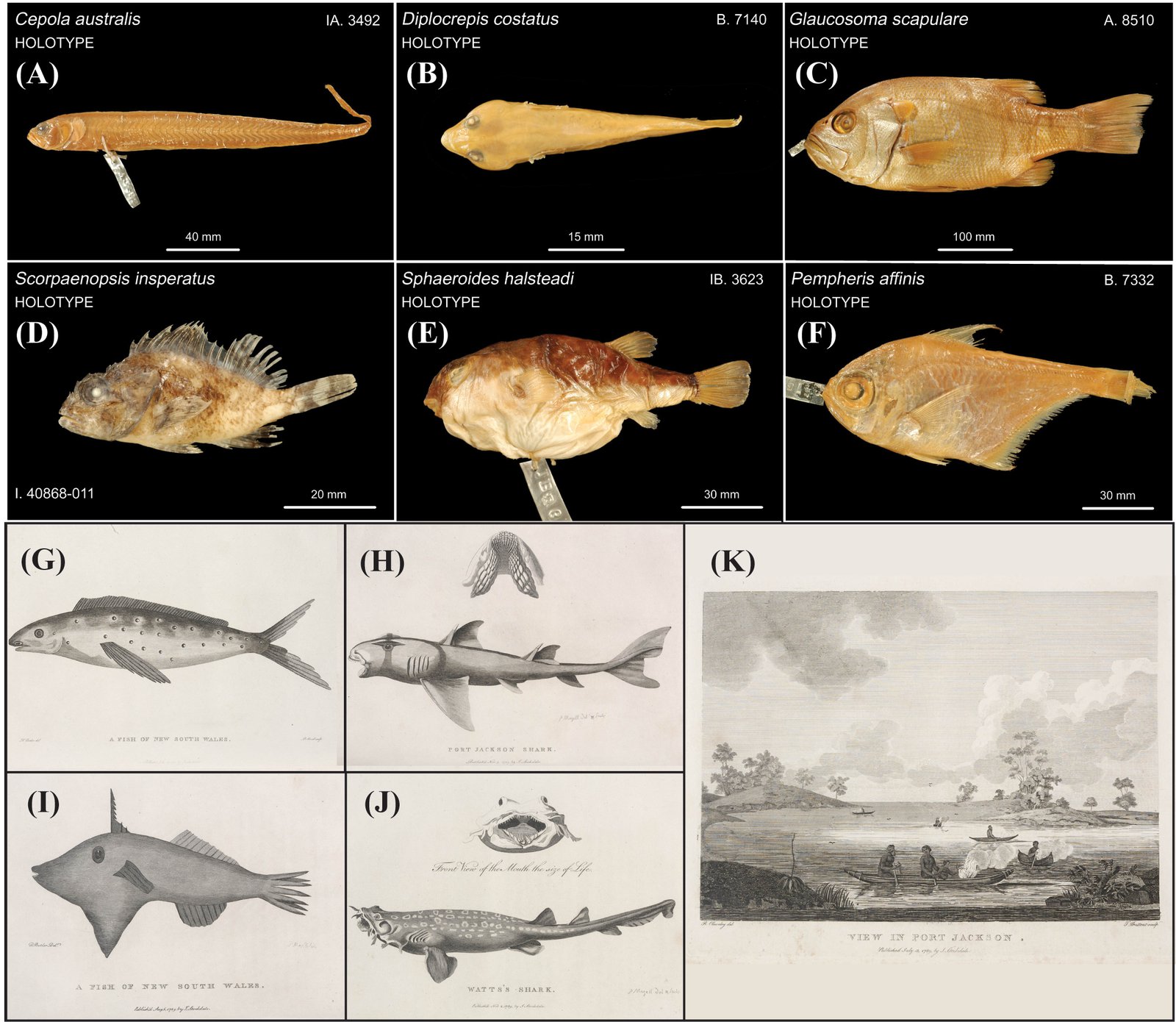

Photos of the holotypes of six fish species taxonomically described from Sydney Harbour (A-F) and historical sketches (G-K) sourced from the collections of the State Library of New South Wales based on Phillip (1789). This includes holotypes for the (A) Australian Bandfish Cepola australis, (B) Pink Clingfish Diplocrepis costatus – now Aspasmogaster costata, (C) Pearl Perch Glaucosoma scapulare, (D) Sydney Scorpionfish Scorpaenopsis insperatus, (E) Halstead's Toadfish Sphaeroides halsteadi – now Reicheltia halsteadi, (F) Blacktip Bullseye Pempheris affinis, as well as sketches of a (G) putative Mahi Mahi Coryphaena cf. hippurus, (H) Port Jackson Shark Heterodontus portusjacksoni, (I) Leatherjacket [Monacanthidae sp.], (J) Spotted Wobbegong Orectolobus maculatus, and (K) view of Port Jackson back in the late 1700’s. Photo credit for holotypes: Mark Allen (Australian Museum).

Image: As above.© As above.

Some fish families were overrepresented in the more urbanized and polluted sections of the harbour. In this study, we used the Sydney Harbour Bridge as an imaginary dividing line. This distinction between the East and West of the habour is based almost entirely on a legacy of poor environmental management practices and waste disposal (yucky dioxins and heavy metals) at sites to the west of Sydney Harbour Bridge. Not-so-fun food fact: the NSW Food Authority warns against eating any fish or shellfish collected west of the Bridge. We found Labridae (wrasses), Mullidae (goatfishes), and Pomacentridae (damselfishes) to the right (east) of it; Eleotridae (sleeper gobies), Gobiidae (true gobies), and Monacanthidae (leatherjackets) to the left (west). Fish families overrepresented west of the Sydney Harbour Bridge have known affinities for freshwater, brackish water, and/or are capable of straddling both fresh and saltwater. These fishes may also be more resilient to marginal environments and residual sources of pollution in the western sections of the Harbour.

Photos of 12 abundant fishes recorded and originally described from Sydney Harbour. Photo credits are as follows: (A) Achoerodus viridis (Steindachner 1866), Erik Schlögl; (B) Ambassis jacksoniensis (Macleay 1881), John Sear; (C) Eubalichthys mosaicus (Ramsay & Ogilby 1886), Erik Schlögl; (D) Eupetrichthys angustipes Ramsay & Ogilby 1888, Erik Schlögl; (E) Hippocampus whitei Bleeker 1855, John Turnbull; (F) Istigobius hoesei Murdy & McEachran 1982, Erik Schlögl; (G) Mecaenichthys immaculatus (Ogilby 1885), Erik Schlögl; (H) Pardachirus hedleyi Ogilby 1916, John Turnbull; (I) Parma unifasciata (Steindachner 1867), Erik Schlögl; (J) Scorpaenopsis insperatus Motomura 2004, Dorothy Lee; (K) Squatina australis Regan 1906, John Sear; (L) Trachichthys australis Shaw 1799, Erik Schlögl.

Image: As above.© As above.

Human impacts on marine biodiversity in Sydney Harbour are many; residential expansion, chemical contamination, recreational fishing, nutrient and turbidity elevation, marine debris and boat traffic, invasive species, habitat modification, and climate change are all part in stressing out our fishes – with no magic solution to fix it. Our exploration of fish records from multiple sources in this study made it crystal clear that we need more collaborative citizen science programs and natural history collections to track the inevitable changes in fishes found in Sydney Harbour.

Dr Joseph DiBattista, Curator, Ichthyology, Australian Museum.

More information:

- DiBattista, J.D., Shalders, T.C., Reader, S., Hay, A., Parkinson, K., Williams, R.J., Stuart-Smith, J., and McGrouther, M., 2022. A comprehensive analysis of all known fishes from Sydney Harbour. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 185, 114239.

- Hutchings, P., Ahyong, S., Ashcroft, M., McGrouther, M., and Reid, A., 2013. Sydney Harbour: its diverse biodiversity. Australian Zoologist, 36, 255-320.

- Phillip, A., 1789. The voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay: with an account of the establishment of the colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island... To which are added the journals of Lieuts. Shortland, Watts, Ball, and Capt. Marshall. J. Stockdale.