Spotting fossil anomalies

Dr Russell Bicknell, our 2021/22 Australian Museum Foundation/Australian Museum Research Institute Visiting Research Fellow, recently explored the trilobites in the Australian Museum palaeontology collection. Russell tells us more about spotting fossil anomalies!

By examining the fossil record, palaeontologists can help us understand how extinct animals functioned and responded to changes in biological and developmental systems. Recently, Dr Russell Bicknell and Dr Patrick Smith (Australian Museum palaeontologist) studied a group of animals called trilobites from New South Wales and found evidence of abnormal structures.

Dr Russell Bicknell and Dr Patrick Smith, AM palaeontologist, studied a group of animals called trilobites.

Image: Abram Powell© Australian Museum

Currently the Australian Museum holds more than 10,000 trilobites in its collection. Of these, 225 are holotype specimens (i.e. they are the standard from which the species derives its name). In Australia alone there are about 1000 trilobite species currently named, hence the AM holds more than a fifth of the country's name-bearing trilobites.

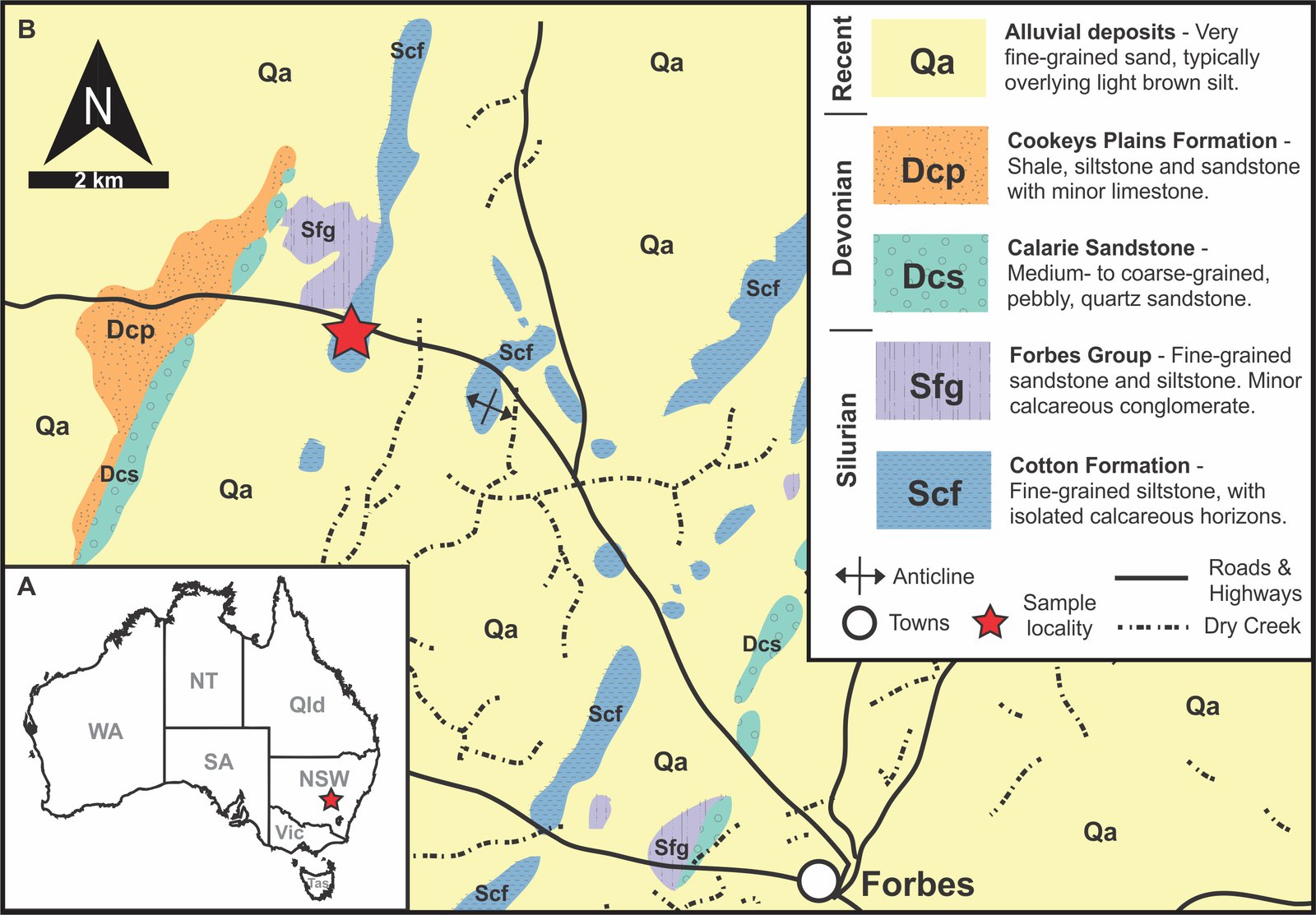

Trilobites are an extinct group of arthropods that had biomineralised exoskeletons. The exoskeleton, made of calcite, is ideal for preserving examples of developmental oddities or injuries due to predation in the fossil record. Although malformed trilobites have been documented, these are often unique, one-off examples. Russell and Pat decided to shift their approach and assess all specimens of the trilobite called Odontopleura (Sinespinaspis) markhami from a particular location, known as the Cotton Formation. This is a Silurian aged deposit (434 million years old), found in rural New South Wales that preserves trilobites in an exceptional level of detail. Furthermore, there are many specimens of this species within the AM collection, making it ideal to uncover possible records of these abnormal specimens.

Geological, stratigraphic, and geographical information for specimen locations and the Cotton Formation.

Image: Patrick Smith & Russell Bicknell© Patrick Smith & Russell Bicknell

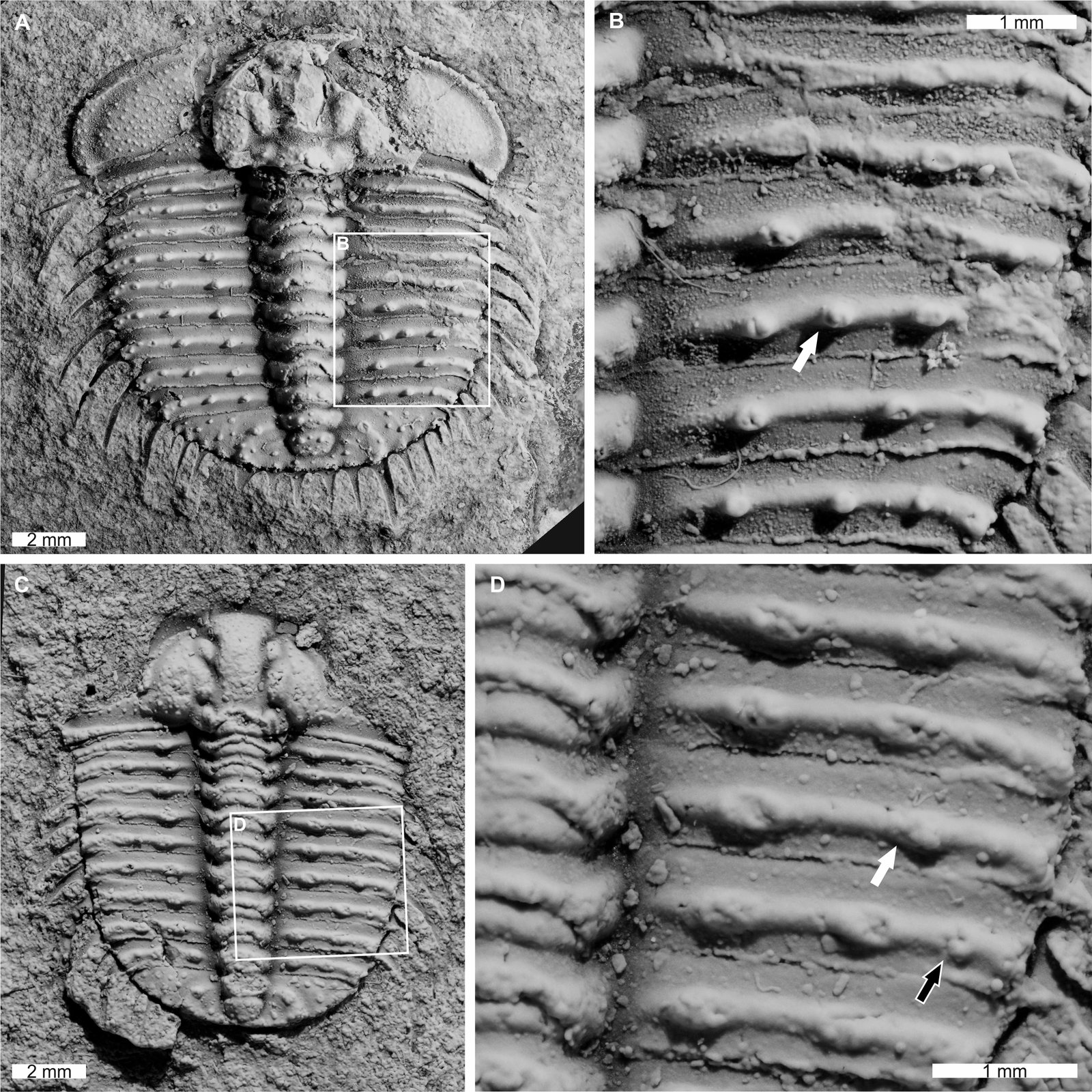

In doing so, Russell and Pat found some unexpected examples of specimens with additional spines. They also showed that these specimens occurred in one of the largest growth stages of these animals. Given that they found no evidence of injuries, Russell and Pat concluded that these abnormal spines likely reflect genetic complications that would not have increased the fitness of these individuals.

Odontopleura (Sinespinaspis) markhami with additional and abnormal structures.

Image: Russell Bicknell© Australian Museum

Examining museum specimens in this way presents important insights into the hidden aspects of the Australian fossil record and how this species experienced and recovered from genetic and developmental abnormalities over time. These studies also show that the largest trilobites may have been important prey species in the ecosystem at this time (for example, by predators such as large nautiloids or starfish in the Cotton Formation). This differs from large trilobites in the earlier Cambrian Period (520-485 million years ago) which often dominated as predators. The switch from large trilobites being “the hunter” to “the hunted” seems to have occurred in the Ordovician (approximately 485-444 million years ago) as is evident in the type and nature of injuries they sustained.

Dr Russell Bicknell, 2021/22 AMF/AMRI Visiting Research Fellow, Palaeontology, Australian Museum.

More information:

- Bicknell RDC, Smith PM. 2022. Examining abnormal Silurian trilobites from the Llandovery of Australia. PeerJ 10:e14308 http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14308

- Bicknell RDC, Smith PM, Howells TF, Foster JR. 2022. New records of injured Cambrian and Ordovician trilobites. Journal of Paleontology, 96(4), 921–929, https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2022.14

Acknowledgements:

The Visiting Research Fellowship was funded by a grant from the Australian Museum Foundation and the Australian Museum Research Institute.