One Fish Two Fish, Red Fish Blue Fish

Examination of historical museum specimens, in both Australian and Indonesian collections, resolve a 170-year taxonomic conundrum.

Pieter Bleeker was a Dutch medical doctor, ichthyologist, and herpetologist extraordinaire. He was a decorated naturalist, his proverbial hat adorned with so many feathers such that it resembled a small bird. Among many of his accomplishments was his work on fishes of East Asia, a monumental compendium that stands today as one of the most important pieces of ichthyological literature. But Bleeker’s work, although extensive, was sometimes nebulous.

Cirrhilabrus solorensis is presently misapplied to several fishes, its true taxonomic identity shrouded in confusion.

Image: Y.K. Tea and H.H. Tan.© Y.K. Tea and H.H. Tan.

He is of course, hardly to blame. The science of taxonomy has grown tremendously since the 1800s, and what was deemed sufficient in the past may not necessarily be representative today. After all, contemporary work is built upon historical foundations, lending to the perpetual state of flux that makes taxonomy so interesting.

The story here begins with Coenraad Jacob Temminck and Hermann Schlegel, in 1845. They, like Bleeker, contributed much toward present day ichthyology and herpetology. In a series of monographs detailing the zoology of Japan, Temminck and Schlegel included an illustration of a little fish with a discontinuous lateral line and long pelvic fins that trailed past the anal-fin origin. The illustration was accompanied by a short description of a new labrid genus, which they called Cirrhilabrus, although strangely enough no species name was given.

Several years later in 1851, Bleeker, in his treatment of the ichthyofauna of the Dutch East Indies, came upon a little fish that was presented to him from Indonesia. To this fish he gave the name Cheilinoides cyanopleura, a new genus and species of labrid. Bleeker’s new species shared many similarities to Temminck and Schlegel’s Cirrhilabrus, though presumably he wasn’t aware of their earlier description. This did not go unnoticed for long, and in 1853, he (Bleeker) assigned a species to Temminck and Schlegel’s Cirrhilabrus (as C. temminckii), thus fixing the type of the genus by monotypy.

In the same year, he described a new species of Cirrhilabrus based on material taken from Lawajong, Solor, Indonesia. He called his new species Cirrhilabrus solorensis, after its eponymous place of origin. His description was brief, though it includes a reassignment of Cheilinoides cyanopleura to Cirrhilabrus (as Cirrhilabrus cyanopleura), thus placing Cheilinoides in the synonymy of Cirrhilabrus and ending its status as valid. To summarise, 8 years after Temminck and Schlegel named Cirrhilabrus, three species of Cirrhilabrus were known.

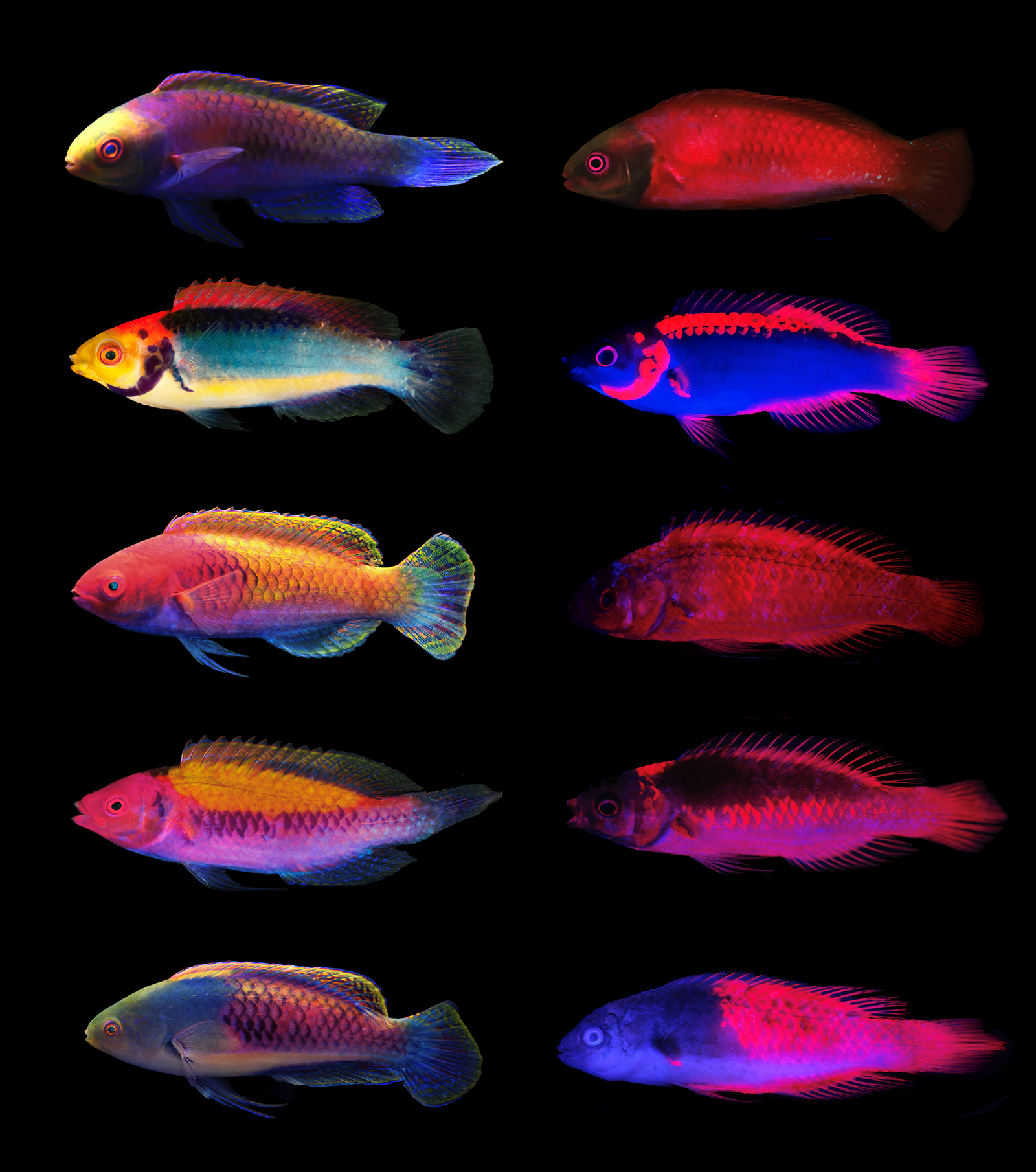

The Cirrhilabrus solorensis complex of fairy wrasses exhibit strong patterns of fluorescence under long wavelengths. These patterns can be used to tell species apart from each other. (A) Cirrhilabrus solorensis; (B) Cirrhilabrus aquamarinus; (C) Cirrhilabrus chaliasi; (D) Cirrhilabrus aurantidorsalis; (E) Cirrhilabrus cyanopleura.

Image: Y.K. Tea, T. Gerlach, and J. Theobald© Y.K. Tea, T. Gerlach, and J. Theobald

Today, the genus has grown to include more than 60 species, accounting for nearly 10% of the entire family. Bleeker’s Cirrhilabrus solorensis still stands, though the scanty description has not withstood the test of time, and today, the name is misapplied to several fishes known from across Indonesia, all of which differ remarkably from each other in coloration patterns. At least two of these disagree with Bleeker’s original description of the nominate species.

So, what do we do? We can call upon one of the cardinal rules of taxonomy here. When in doubt, always consult the holotype. The holotype is the single specimen upon which the description and name of a new species is based. Unfortunately, the holotype of Cirrhilabrus solorensis is stored in the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, Netherlands. With travel restrictions in place, travelling there to examine it was not an option. Fortunately for us, our colleague Esther Dondorp was nice enough to send us high-resolution images of the holotype.

Cirrhilabrus solorensis and other closely related species from its complex are unusual among species of Cirrhilabrus in having blue preserved coloration. AMS.I 46115–048.

Image: Australian Museum© Australian Museum

The images of Bleeker’s holotype revealed several unique characters that were not detailed in his original description, such as the characteristic blue coloration the species takes on when preserved in alcohol. This is where the Australian Museum’s extensive collection of preserved fishes comes in handy. It took no time at all to track down jars of Cirrhilabrus solorensis held in storage at the Australian Museum, and also other regional museums such as the Western Australian Museum. Detailed examination of these specimens corroborated what we know of these fishes based on their live coloration, that the name Cirrhilabrus solorensis is indeed a catchall for several new species masquerading under the same moniker. These new species were separated from C. solorensis and described as C. aquamarinus and C. chaliasi. The former draws attention to the arresting coloration of the males, in ludicrous aquamarine, to which no other Cirrhilabrus remotely resembles. The latter is a patronym given in honor of Vincent Chalias, a Balinese based biologist who is a fierce proponent of sustainable aquaculture.

Members of the Cirrhilabrus solorensis species complex. Cirrhilabrus solorensis is depicted in (A), and the two newly described species, C. aquamarinus (B) and C. chaliasi (C). The other species in alphabetical order are C. cyanopleura, C. ryukyuensis, C. cf. ryukyuensis, C. luteovittatus, C. randalli, and C. aurantidorsalis.

Image: Photographs by T. Cameron (A), M. Rosenstein (B), K. Nishiyama (C), E. Schlogl (D), S. Harazaki (E), and G.R. Allen (F–I).© Photographs by T. Cameron (A), M. Rosenstein (B), K. Nishiyama (C), E. Schlogl (D), S. Harazaki (E), and G.R. Allen (F–I).

It goes without saying that museums hold the keys to unlocking windows of our past, providing a wealth of information that otherwise lost to the passage of time. The importance of historical material cannot be emphasised enough, with museums simultaneously acting as historic time capsules and centres for cutting-edge research.

These historic repositories allow us to resolve difficult taxonomic quandries such as this, with implications that can alter the way we manage biodiversity and assess endemic species. After all, we can’t conserve what we don’t know, and taxonomic revisions like these help shed light on potentially new species hiding in plain sight.

Yi-Kai Tea, PhD candidate, University of Sydney; 2019–20 AMF/AMRI Postgraduate Award Recipient, Australian Museum Research Institute.

Acknowledgements

This study was done in collaboration with Gerry Allen from Western Australian Museum, and Muhammad Dailami from the Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia. We thank Amanda Hay and Kerryn Parkinson (AMS), Glenn Moore and Mark Allen (WAM), Ilhan Vemandra Utama (MZB), Kelvin Lim and Heok Hui Tan (ZRC), and Michael Hammer (MAGNT) for curatorial assistance, loan of specimens, and provision of registration numbers. Esther Dondorp provided photographs of the holotype of Cirrhilabrus solorensis. We thank Amanda Hay and Kerryn Parkinson for X- radiographs. Joseph Rowlett provided useful distributional data. We would like to also thank Vincent Chalias, Hiro Chan, Michael Hammer, Shigeru Harazaki, Joe Heard, Kevin Kohen, Francois Libert, Kazuhiko Nishiyama, Sabine Penisson, Erik Schlogl, Heok Hui Tan, Mark Rosenstein, Rob Whitton, and the late John Randall for providing excellent photographs used in this study. Nico Michiels, Tobias Gerlach, and Jennifer Theobald provided photographs and correspondence regarding autofluorescence of Cirrhilabrus. Anthony Gill, Luiz Rocha, and Brian Greene provided useful comments that improved the quality of this manuscript.

Reference:

Tea YK, Allen GR, Dailami M. 2021 Redescription of Cirrhilabrus solorensis Bleeker, with description of two new species of fairy wrasses (Teleostei: Labridae: Cirrhilabrus). Ichthyology & Herpetology, 109: DOI: 10.1643/i2021022.