A six-year journey of discovery, friendship and loss: Amphoton bicknelli

The story of a beautiful trilobite

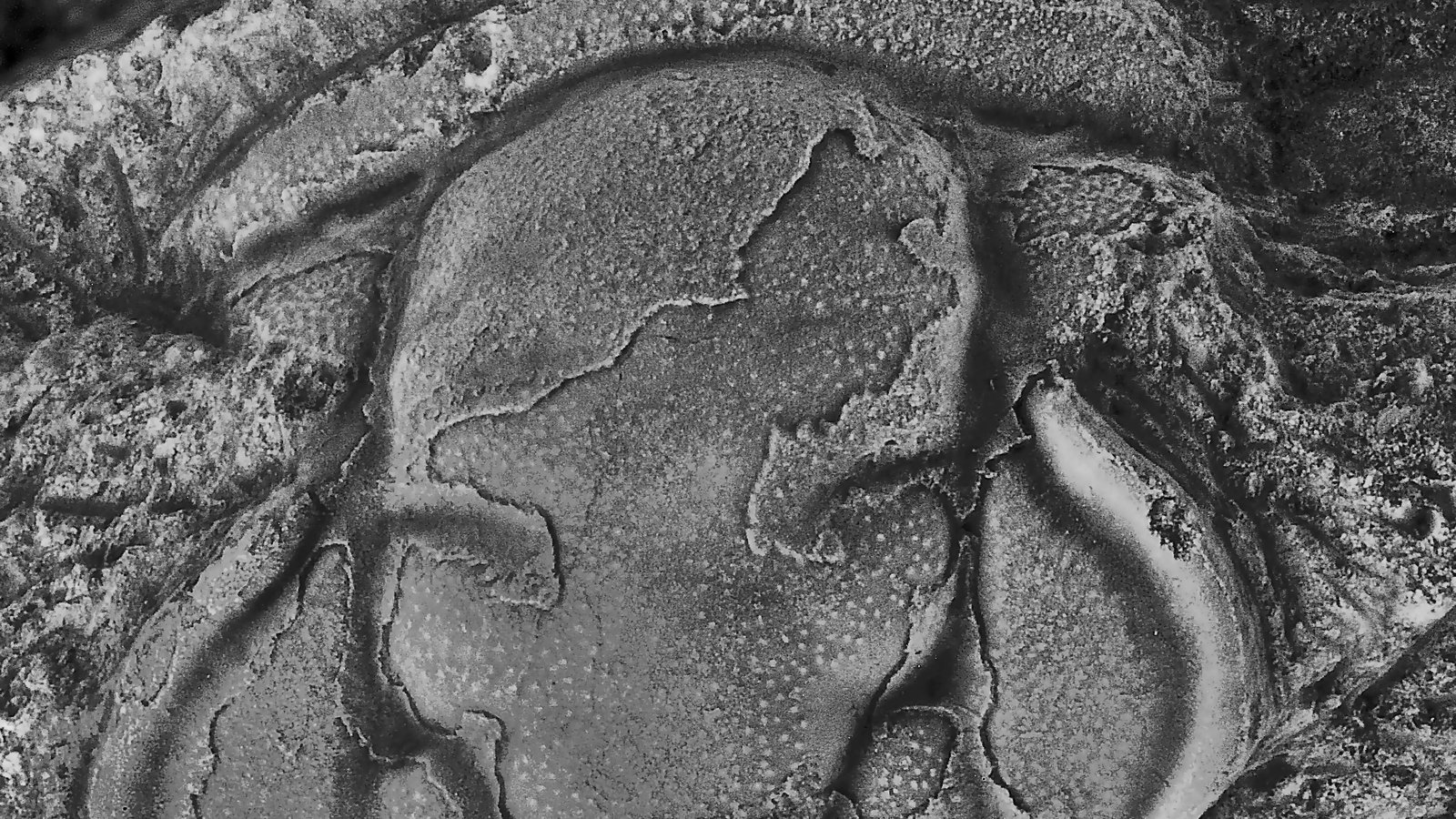

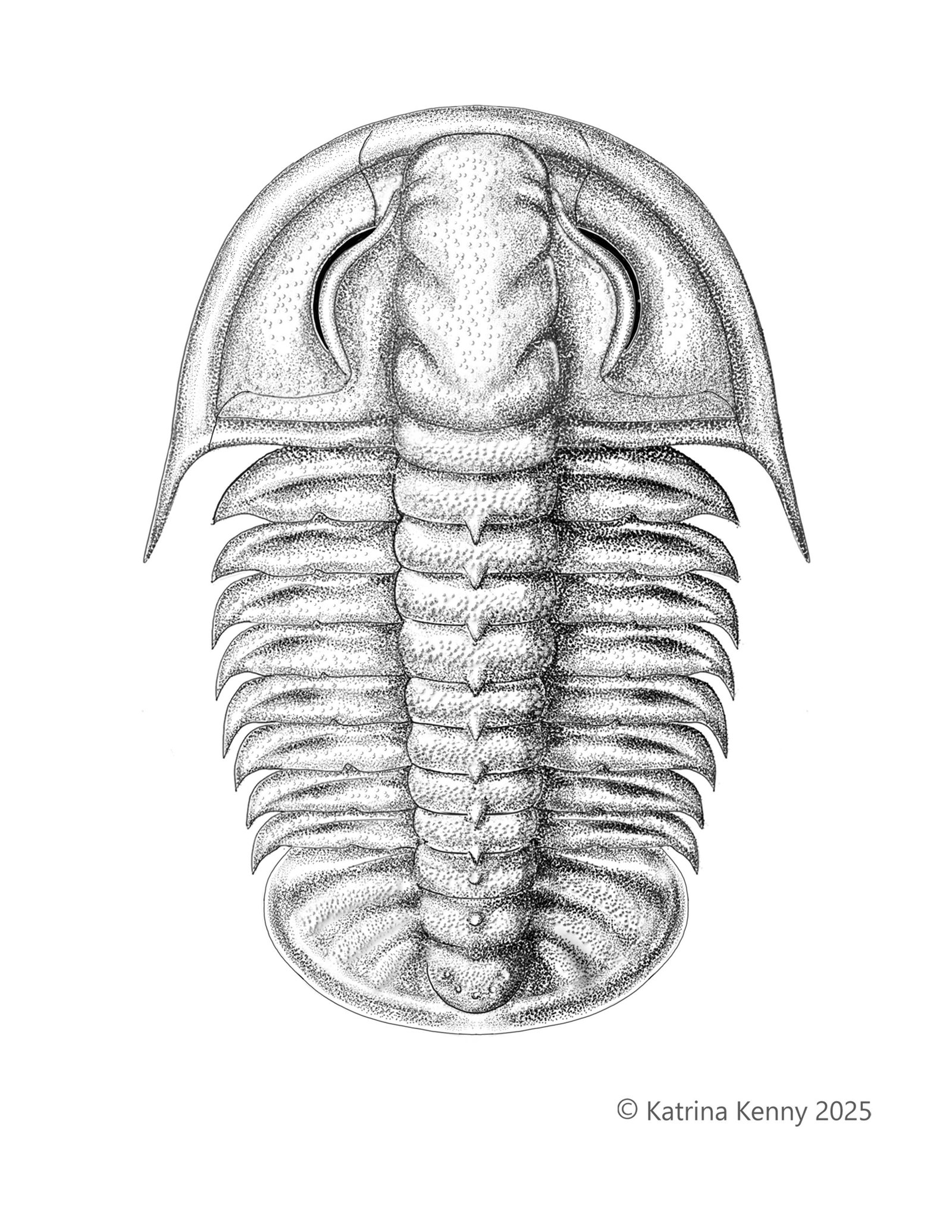

Amphoton bicknelli is a newly described and unusually beautiful trilobite from the Tasman Formation in New Zealand, recently named in honour of Dr. Russell Bicknell (a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA). Dr Bicknell is a New Zealand-born palaeontologist and long-time friend and collaborator who I've known and worked with for many years. The discovery of this new species formed part of a larger study that I had the honor of leading, which described the oldest fossils in New Zealand, including trilobites and agnostids from "Trilobite Rock" in the Cobb River Valley, northwest of Nelson on the South Island. In the world of palaeontology, finding a new species is always a momentous occasion. Trilobites, ancient creepy crawlies of the seas, are prized in palaeontology for helping us date and decode Earth’s deep past. The story behind the naming of this new trilobite, however, is arguably just as interesting, it's a tale of shared friendships, losses and the enduring passion for exploring the mysteries of deep time among fellow scientists.

© Katrina Kenny

A simple question

The journey to this discovery began quite serendipitously. It started when I accidentally contacted Russell about an unrelated trilobite paper we were working on together. His response was unexpected but thrilling: "I have material from 'Trilobite Rock' in NZ. I have not yet worked on it but...would it interest you?" This simple question set off a chain of events that led me to Roger Cooper, a previous colleague of Russell's and a researcher at the New Zealand Geological Survey (GNS).

Special specimens

Although Cambrian trilobites in New Zealand had been known since the late 1940's, there had not been any systematic collecting of the material. Yet, Roger acquired a vast number of specimens while geological mapping the entire area in the 1960s and 70s, during his early career. These specimens had never been examined in detail by scientists, only having been photographed in coffee-table style books on the generalised subject of "New Zealand fossils". Despite this lack of research, the specimens would prove to be fundamental in developing a better understanding of the early history of New Zealand's formation as a landmass, and its connection to other continents. This significance wasn't lost on Roger, hence he invited my wife and I to New Zealand to examine the collections at GNS, giving us a chance to explore the local geology and the stunning landscapes of the South Island. It was during this time I developed a close friendship with Roger, which continued once my wife and I returned to Australia.

In his honour

Only a year later, the project took on a deeper significance with Roger passing away after a long battle with illness in 2020, during the first rounds of COVID lockdowns. This was a heavy blow, but it also strengthened my resolve to complete the study in his honour. With the help of his field notes and the support of my co-authors, John Laurie (from Geoscience Australia) and Jim Jago (from the University of South Australia), both of whom also knew Roger, we persevered. After six years of dedicated work painstaking photographing every aspect of these amazing fossils, we finally completed the study, which documented a whooping 59 species from this one little area of New Zealand. Among these were five new species which were completely unknown to science!

Celebrating collaborations

While you'd think it would make sense to name a new species after Roger, new species names don't work like that. There's an unwritten rule among species naming scientists (i.e. taxonomist) that we can't call anything new after ourselves (presumably so we don't get big heads!). Since Roger was already an author, having collected a lot of the fossil material himself, we decided instead to honour the other New Zealand-born scientist and friend who was involved, Russell, as he'd arguably initiated the project when contacting me. Giving it the naming Amphoton bicknelli was a real highlight, and I felt it symbolised the strong friendships that scientific collaborations can build in our work, and which drives our new discoveries.

Dr Patrick Smith, Technical Officer, Palaeontology in New Zealand within the same mountain range where the fossils were found.

Image: Patrick Smith© Patrick Smith

The human side to science

This project is a testament to the human side of science. While we often think of scientific research as a cold, unemotional pursuit, it is, in fact, deeply personal and filled with stories of happy accidents, enduring friendships, and poignant losses. The discovery of Amphoton bicknelli is not just about adding a new species to the fossil record (as is typically depicted); it is a celebration of the connections and shared passions that make science a profoundly human endeavor. It is these connections that inspire us to continue exploring and understanding the natural world.

Dr Patrick Smith: Technical Officer, Palaeontology