Feathers of the Gods: Is it a Bird?

© Australian Museum

Is it a bat? Is it a plane? If you are an air traveller, you probably have more to do with museums – especially ours – than you think!

This story is an extract from our new book, Feathers of the Gods and Other Stories from the Australian Museum, in which scientists, collection managers, coordinators, conservators, archivists and volunteers share their favourite tales inspired by our collections.

Since humans started flying in aircraft, sharing the skies with wildlife has been a hazard worthy of management and mitigation. Even the famous Wright brothers experienced birdstrike.

Their diaries record an incident that occurred on one of their early flights, in 1905. During the flight, which lasted a mere 4 minutes 45 seconds, Orville Wright chased a flock of birds and subsequently collided with one of them.

With the amount of travel we do in the 21st century and with increasingly quiet aircraft, collisions between planes and birds or bats are inevitable. In the past decade in Australia, the rate of aviation wildlife strike has more than doubled.

Such collisions not only cost the industry millions of dollars each year, but can also be extremely dangerous: in 2009 a passenger plane was famously forced to land on New York’s Hudson River after a flock of geese were ingested into its engines.

The aviation industry now uses every tool in the toolbox to get the most precise picture of which species are involved in aircraft collisions. With accurate data, management efforts can then be targeted on the species of highest risk.

Strategies to mitigate collisions include: modifying the habitat around airports to make it less attractive to birds; attempting to frighten away birds and bats using sounds, fireworks, decoy predators or dogs; and altering flight paths.

Most air travellers would not immediately think that the Australian Museum makes a significant contribution to air safety. The Australian Centre for Wildlife Genomics at the Museum has developed an innovative program in collaboration with the aviation industry to assist with the DNA identification of species involved in wildlife strike (see image overleaf).

We offer the unique combination of a state-of-the-art genetics laboratory, taxonomic expertise, animal collection and distribution data, and an extensive frozen tissue collection.

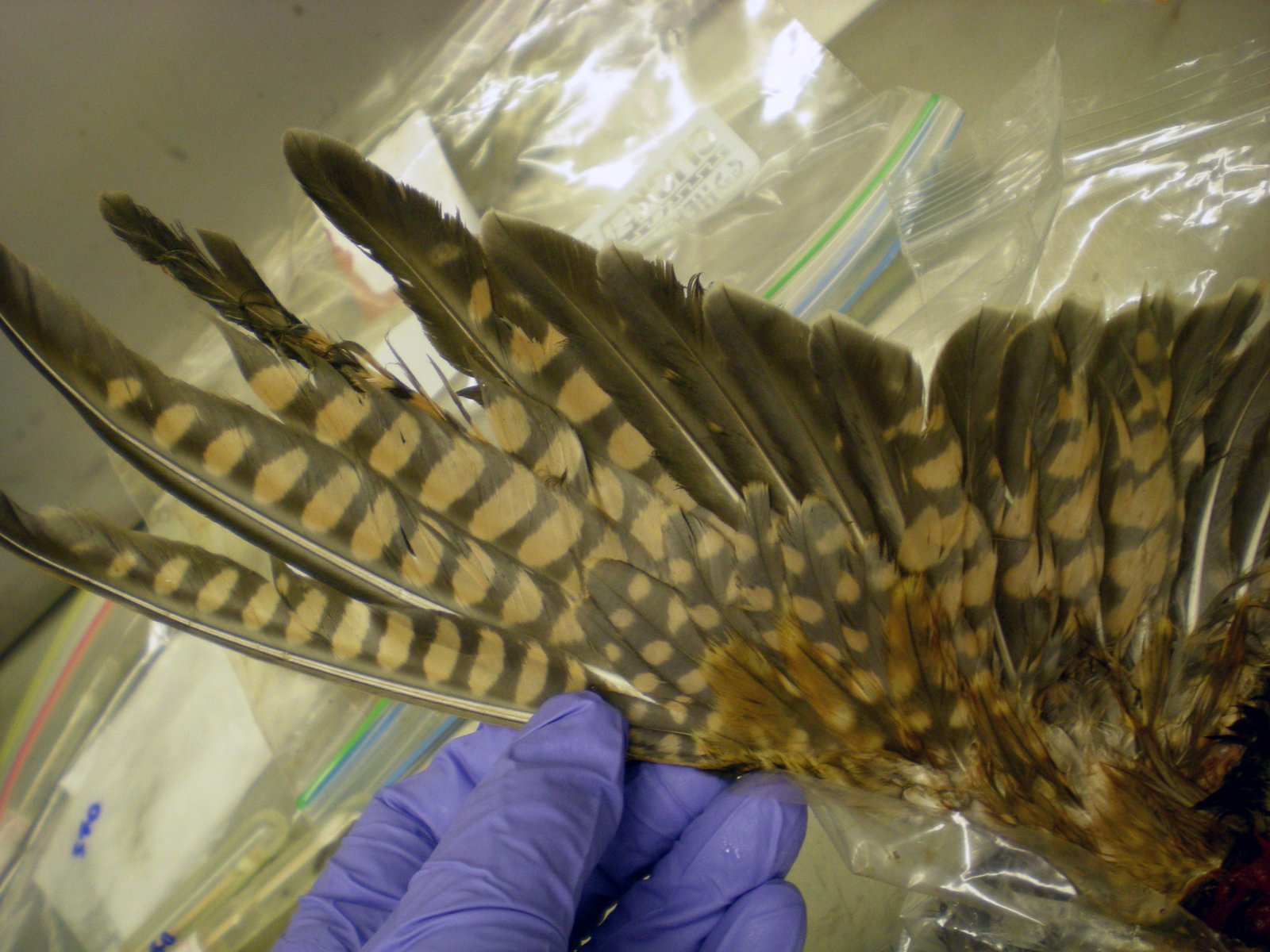

Every week, the Australian Centre for Wildlife Genomics receives wildlife strike samples from a variety of Australian airports, including those of the Defence Force. Typically, the samples are unrecognisable. They can be blood, skin, feathers or fur – hence the need to use DNA analysis, together with the Museum’s extensive animal reference collection, to obtain an accurate identification.

Since the inception of our work in Australia in 2005, we have continued to work with the aviation industry to improve their species identifications and minimise the proportion of ‘unknown species’ recorded in aviation wildlife strike. During this period, the team at the Museum has identified at least 150 species involved in aviation wildlife strike either in Australia or elsewhere with an Australian aircraft.

At the Australian Museum we are proud to have developed such a groundbreaking and useful identification program. Our work allows the facilities and collections of the Museum to benefit a whole industry and its customers.

Dr Rebecca Johnson

Head

Australian Centre For Wildlife Genomics