Douglas Grant, Aboriginal Digger

Elizabeth McKinnon searches for the true story of Douglas Grant, one of many Aboriginal men who enlisted in World War I.

From the very beginning, I was captured by Douglas Grant’s story. From his early adoption by a Museum taxidermist to an accomplished but tragic life, he was torn between two worlds as an educated Aboriginal man in white society in the early twentieth century.

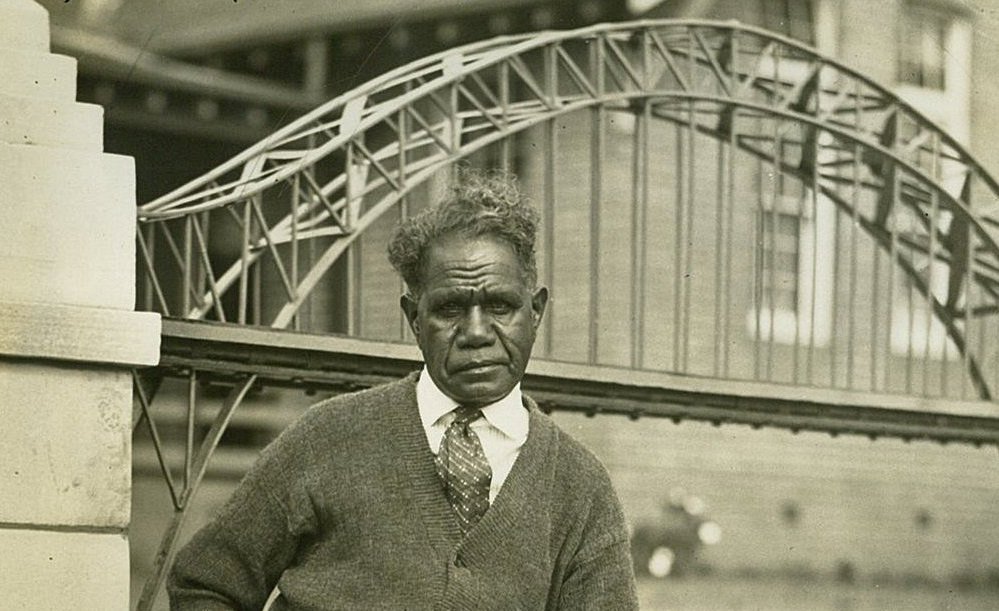

Private Douglas Grant

Image: Unknown© Out of Copyright

Adoption

Among the varying published accounts, it is difficult to discover the truth behind his adoption, but the common facts are that in 1887, Robert Grant, a taxidermist, was collecting specimens with his wife and a colleague in the Bellenden Ker Range, Far North Queensland, when an altercation erupted in nearby Atherton between local Aboriginal people, gold miners and police. It escalated into a massacre of which the toddler Douglas was the only Aboriginal survivor.

Was Douglas saved by one of the very miners who had just shot and killed his parents? Or did Grant himself save the boy at gunpoint just as his head was about to be dashed against a tree by an Aboriginal tracker? Such newspaper accounts written long after the event seem fanciful and melodramatic, but the Grants did take the orphaned boy to the family home in Lithgow where he was raised as one of their own.

Lithgow at this time had a strong Scottish community, and Douglas was raised to speak with a distinct Scottish burr. He had an early interest in entomology, lodging several lots of insect specimens he’d collected from the Lithgow area with the Museum in 1894 and 1895. The family relocated to Annandale just west of Sydney in 1897 when Robert Grant was appointed as taxidermist to the Museum.

War

Douglas showed an early aptitude for drawing, and in 1897 he won first prize for a drawing of Queen Victoria during her Diamond Jubilee Exhibition. He attended Scots College in Sydney with his brother, Henry, and left school to work as a draughtsman for Mort’s Dock and Engineering Company in Sydney. His brother meanwhile followed in his father’s footsteps to become a taxidermist at the Museum, rising to Senior Taxidermist in 1909, a post he held until 1942.

By the outbreak of World War I, Douglas was working as a wool classer at the historic ‘Belltrees’ property near Scone in the NSW Hunter Valley. He enlisted in 1916 with the 34th Battalion and gained sergeant’s stripes but was prevented from leaving for the front by regulations banning Aboriginals from enlisting. But Douglas re-enlisted the following year and this time served in France as a private with the Australian 13th Battalion, only to be wounded and captured in April 1917 during the first Battle of Bullecourt. With his dark skin, Scottish accent and educated manner, Douglas was something of an ethnological curiosity to his German captors, and his head was studied, measured and, reportedly, modelled in ebony.

To his comrades, Douglas was not an Aboriginal man in a white army; he was just a fellow Digger. Douglas recalled later in life that, ‘the colour line was never drawn in the trenches’. The men voted him the Red Cross representative to distribute ration parcels, a job he performed diligently. His intellect, sense of humour and love for literature made him popular among his peers in the camps.

Beyond the line

Following the war Douglas went to live with his sister in Lithgow, working at the Small Arms Factory. With some of his fellow soldiers, he broadcast sessions on the local radio and became secretary of the Lithgow sub-branch of the RSL. But life became difficult for Douglas and other Indigenous men who went to war. Some time after 1928, Douglas lost his job at the factory and found it difficult to obtain stable work. As an Aboriginal, he was not entitled to the grants or benefits that other returned soldiers could obtain.

For a time he took part in Anzac Day parades with his trench mates, until the inequality of life took hold. In 1929, he wrote an article which appeared in the Sunday Pictorial reflecting on the infamous massacre of 31 Aborigines the previous year in Coniston, NT, and on the social injustice in Australia and the difficulties faced by ‘half-castes’.

He later worked as a clerk at Callan Park Hospital where many returned soldiers were housed.

In the 1940s an acquaintance from the Museum, James Kinghorn, was marching with his unit when he saw Douglas sitting under a tree in the Domain. He broke ranks to ask him why he was not marching, to which Douglas replied, ‘I’m not wanted anymore, I don’t belong. I’ve lived long enough’.

Douglas’s foster brother passed away in 1944 in tragic circumstances. Douglas died six years after his brother, following a stroke. He had been a resident of the Salvation Army Home on Bear Island at La Perouse.

Struggle

There is renewed interest in telling the true story of Aboriginal involvement in World War I, with the play Black Diggers premiering at the 2014 Sydney Festival (with Douglas Grant’s story included). Estimates of Aboriginal involvement in the war vary from 400 to 1000 men, yet it is an overlooked part of Australia’s history.

Much of what I’ve read about Grant in researching this article has been from the perspective of white society. It was difficult to discover a clear picture of the man among the available conflicting and often patronising accounts. However, he emerges as a man who struggled to find his identity; a decent man, educated and loyal, who fought for his country and worked for values of greater equality, support for the disadvantaged and Aboriginal rights.

Elizabeth McKinnon, Museum Studies Intern

Douglas Grant was a draughtsman before he became a wool classer, then a soldier. Here he sits beside the war memorial he designed at Callan Park Hospital, Rozelle in 1931.

Image: Sam Hood© State Library of NSW